By Alex Paul

Last week I met a woman with an amazing life story. Now in her 90s, during World War II she worked on a B-17 production line, building planes that flew in the battle to liberate Europe. The 70th anniversary of D-Day on June 6th was a poignant moment to remember the sacrifice of those who served in WWII. Among the world leaders in France for the commemorative events, there was one head of state present who served in the War: the UK’s Queen Elizabeth II.

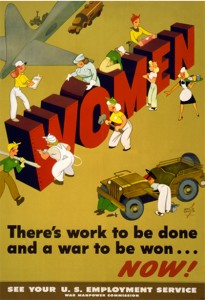

While the role of men in WWII is well-documented through film and books, my meeting with a female veteran got me thinking about the much less-discussed role of women in the war, which included around 350,000 in uniform alone – and many others in non-uniformed roles too. They served with distinction across Allied forces, but their contribution is often forgotten.

For example, in the United States, over 1,100 female pilots joined the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs). They delivered new planes from factory to military bases, tested refurbished ones and towed targets for air and ground gunners to aim at in training with live ammunition. In the words of General Henry Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Force, they put it “on record that women can fly as well as men.”

Meanwhile thousands of women also served in the USSR air force. Unlike other Allied forces though, Soviet women served in combat units like the 588th Night Bomber Regiment. The Regiment flew over 30,000 night-time raids on its way to becoming the most decorated female unit in the Soviet air force. It was so feared by the Nazis, who called them “Night Witches”, that they awarded an Iron Cross to any Luftwaffe pilot who downed one of the Regiment’s flimsy plywood and canvas planes.

Artist: Vernon Grant. For the U.S. Employment Service, War Manpower Commission. Under license from Creative Commons.

Women also served with distinction in some of the more secretive roles of the War. Records show that the British dispatched more than 80 female secret agents to France before D-Day. But many stories of their courage have been lost over time. “I think the contribution that (the women) made to the liberation of their countries needs to be told” commented Bernard O’Connor, a historian specializing in British secret operations in France, at the unveiling last year of a memorial dedicated to these women. The contributions of women like Annie Sofie Østvedt, a leading figure in the Norwegian resistance movement who commanded a group of 3000 men in southern Norway, should also not be forgotten.

Finally, women were vital in reporting on the war in Europe. News correspondents like American Martha Gellhorn, who worked for Colliers magazine, ignored a ban on women on the frontlines to land in France on D-Day itself. She stayed with the advancing Allies all the way to Germany, filing stories from Normandy, newly liberated Paris and concentration camps in Eastern Europe. The stories of these brave women correspondents are credited with moving war reporting towards a focus on the impact of war on the people and civilians involved, rather than on set-piece battles between armies.

WWII was a conflict where women served the Allied world effort with honor and distinction. Yet the world has been slow to recognize their service. It was only in 2010 that their service of WASPs in America was fully honored when President Obama awarded them the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian award. Sadly fewer than 300 WASPs were still alive to see it.

President Obama signing S.614, a bill to award a Congressional Gold Medal to the Women Airforce Service Pilots, in the Oval Office Wednesday, July 1, 2009. Photo credit: Official White House photo by Pete Souza, under license from Creative CommonsWith the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII next year, it is worth reflecting on whether society fully recognizes the contribution of women in WWII, especially as their stories tend to be forgotten. As Baroness Betty Boothroyd, a member of the UK Parliament said at the unveiling of the British memorial to women who served in WWII, "I hope that future generations who pass this way will ask themselves: 'what sort of women were they?' and look at our history for the answer." Let us ensure that history has the answers ready.

Alex Paul is a WIIS Program Assistant. He has just completed a Master’s in International Relations at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, New York. His research focuses on security provision and reform in post-conflict states.

Banner photo: Personnel of the Canadian Women's Army Corps at No. 3 CWAC (Basic) Training Centre (April 1944). Under license (Creative Commons) from Canada, Department of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada, PA-145516 /.