There were two overarching themes that resounded throughout the discussion: the importance of (1) women helping other women, and (2) “taking the lead.”

Women helping other women:

Koch began the discussion with a message of gratitude and recognition of the importance that mentors have played in her own professional development. No one was more influential in helping shape her career than the mentors she found in the WFPG while she was a masters student at Johns Hopkins. “The WFPG took me by the hand,” Koch said. “Those women were instrumental in helping me become the person I am today.” People’s capacities to give back go beyond the changes they make in the world as professionals. Mentorship, Koch said, can be the most powerful way of making an impact, both within your profession and in the world at large. Now, more than ever, with the global gender gap (employment and income) increasing to 59{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} over the past four years,[1] women stand to benefit the most from mentorship. Women have to help other women succeed, from providing networking connections, to hiring and training.

Koch used this theme to set out the primary goals of the discussion: to educate participants about the myriad opportunities that are available across the 36 UN peacekeeping operations[2] for senior-level female professionals, and to dispel misconceptions about careers in global peacekeeping that make women wary of considering them.

Here is what we learned:

Myth 1: Peacekeeping is dangerous, and I have no military background or other experience in conflict.

- There are two main divisions across all UN Peace Operations: (1) the Blue Helmets (military members who enter conflict situations to physically quell disputes), and (2) the civilian force. While the Blue Helmets are the archetypical image of UN peace operations in many respects, the Blue Helmets actually form the smallest component of all peace operations. The true backbone of peace operations lies with the civilian force, which provides political, logistical, and administrative support to the missions. While the Blue Helmets can be exposed to considerable danger, civilians work with community members to assess people’s needs in post-conflict situations, promote organization of elections and other measures to restore political stability, protect human rights, and assure proper implementation of peace agreements, among other tasks. To date, no civilians have died while on mission.

Myth 2: Even if I want to work as a Civilian, I probably don’t have the skills they are looking for.

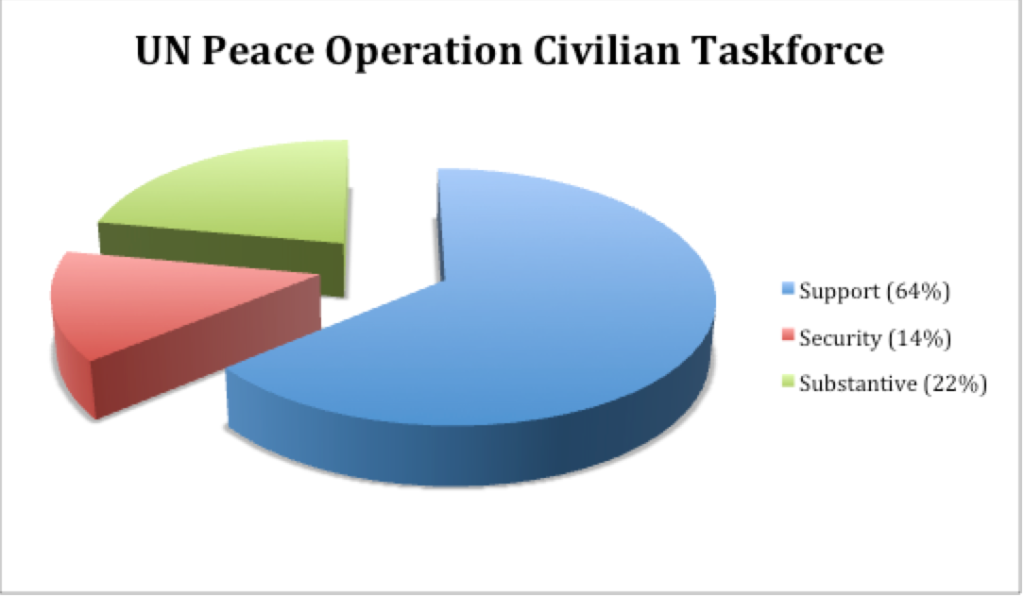

- Think again. The civilian force is comprised of three pillars: support staff, security staff, and substantive staff. The security staff calls for professionals with diverse skill sets, including analytics and crisis management. The substantive staff looks for women who have community support knowledge, which can range from experience working in women’s protection, child protection (i.e. social work), or in military or police forces. Lastly, the support team that forms the large majority of civilian work requires professionals with many types of experience, including supply chain, finance, IT, and engineering. Among all of the support taskforce profiles, IT and engineering /STEM-related fields have the biggest gender gaps, requiring greater levels of female participation to achieve gender parity.

Myth 3: I don’t have any UN experience, or any substantive foreign policy experience. I wouldn’t be considered.

- “Women from non-UN institutions can contribute many new skills and fresh ideas to peace operations,” Koch said, which play a key role in augmenting the scope and efficacy of peacekeeping missions. While some women leaders in UN Peacekeeping began their careers in foreign service, like Barrie Freeman, Chief of Staff for the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic, others began in the private sector. For Cassandra Nelson, the current Director for Strategic Communications and Public Affairs at the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia, the communications experience that she began to accumulate during her first job in Entertainment/Media at Price Waterhouse was crucial to landing her position with the UN. Not having a foreign assignment is challenging, Koch said, but resilience is the ultimate key.

Myth 4: I’m not going to make a difference.

- The first question should be: what kind of difference is most important to you? A difference in numbers, to move closer to gender parity? Or, a difference in effect, based on what you accomplish as a professional?

- Achieving gender parity is certainly a tall order when considering that the current UN gender gap stands at 72{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} men v. 28{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} women, and that the representation of women since the release of UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 has remained stagnant. The gender gap widens when moving up in professional rank; while lower-to-mid-level P2 and P3 international jobs account for the highest percentage of female staff members (42{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} and 32{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} respectively), only 92 women hold P5-level jobs, whereas men hold 297 P5 positions. “Even if we hired a woman for every single vacant position, we would not achieve gender parity,” Koch said.

- While it is uncertain that we can meet the Secretary General’s goal to achieve gender parity by 2026, increased women’s involvement in UN peacekeeping will create a much more immediate impact by making peace operations more successful. In addition to benefiting from women’s different approaches to conflict management and fresh ideas for out-of-the-box-thinking, peacekeeping operations are significantly more effective when their composition more closely reflects the community being protected. Female peace officers can build stronger rapport with mothers and children in the communities they are assisting, allowing them to gain more information that is critical to developing realistic and long-lasting peace resolutions that will serve a community’s unique needs.

“Taking the lead:”

This concurrent theme was particularly salient to Koch’s advice on making the transition from non-UN /non-foreign policy focused positions to a career in peacebuilding. Barrie Freeman sent a text message just before the session began with a message that she wanted the group to leave with: Don’t be afraid, take the lead. Koch highlighted Freeman’s message in reminding the audience that women tend to wait to apply for a job until they are “approximately 125{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} sure that they meet all criteria, whereas men apply for everything.” Koch encouraged women to apply for more than one position, reiterating the importance of being your own best advocate by selling your skills and strengths.

Additional key points include:

French is the future:

Estimates indicate that by 2050, French will be spoken by 750 million people worldwide.[3] In global peacebuilding, French is certainly the language of the future. While English remains the predominant language in UN operations, speaking French is the single most sought-after skill to bring to the table, whether you are a fluent speaker[4] or have working knowledge.[5] Arabic is also highly recommended, though French remains in highest demand, as 80{5f0f57c44bc297437706deade099e6516fe1db1b31ab604b564d60e47f160dcd} of peace operation placements are in African communities where French is one of the maternal languages.

Own your diversity.

I asked Koch what advice she would give to younger and mid-level professionals on how to best prepare them for a future job in UN peacebuilding /global security and, more specifically, what opportunities existed for women with legal backgrounds. Koch addressed the legal question first, discussing how there are many opportunities for lawyers in UN missions. Not only does the UN have its own legal office, each mission has its own legal team of 10-15 members who handle everything from investigations (particularly sexual exploitation and abuse claims of community members against peacekeeping soldiers, and violations of humanitarian law) to other issues that are not thought about as often, such as cultural heritage disputes that arise in conflict and post-conflict situations. Koch noted that many officers have a legal background before coming to the UN, regardless of whether they serve a legal function in the field as peace officers. Practicing law equips women with many valuable skill sets that help peace missions be more effective. Having experience in transnational and/or international law is particularly useful, however, as many of the legal issues that arise can be governed by more than one jurisdiction.

With regard to general advice for women in earlier stages of their careers, Koch once again emphasized the importance of learning French, but also recommended that women focus on developing technical experience in different types of conflict resolution. This can be achieved in any professional experience that involves understanding what drives conflict, what strategies/designs can most effectively lead to resolution and those that lead to resistance, and how to reintegrate parties affected by conflict after resolutions are concluded. Among the many professions that help cultivate this skill, some examples include law enforcement, law, policymaking, and even business management, to name a few. Koch’s bottom line: just as there is no single perfect set of qualifications for a career in peacebuilding, there is no perfect way to get there. Own your personal and professional diversity, and take the lead.

This year’s UN Peace Operations Senior-Talent Pipeline opened on June 15, 2017. For further information about the Pipeline, please visit: https://www.impactpool.org/un-peace-operations/swtp

The video recording and presentation materials from the June 12 Discussion can be found here and here.

[1] Jill Treanor, “Gender pay gap could take 170 years to close, says World Economic Forum,” The Guardian (Oct, 25, 2016), accessed June 13, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/oct/25/gender-pay-gap-170-years-to-close-world-economic-forum-equality

[2] Seventeen of these operations involve active military intervention, while nineteen focus on political tactics.

[3] Pascal—Emmanuel Gobry, “Want to Know the Language of the Future? It Could be… French,” Forbes (Mar. 21, 2014), accessed June 12, https://www.forbes.com/sites/pascalemmanuelgobry/2014/03/21/want-to-know-the-language-of-the-future-the-data-suggests-it-could-be-french/#2e90cc776d58

[4] Fluency, in this context, means that you can effectively communicate with ministers and other high officials, draft peace agreements and legal documents, etc.

[5] Working knowledge, Koch explains, means that you can effectively interact with the local community.

About the Author:

Spencer Beall is a Legal Research Assistant at WIIS Global. She is a 3rd Year JD/LLM Candidate at Georgetown University Law Center, specializing in transnational privacy/cybersecurity law and its impact on global security.

Contact Spencer Beall by email at: sbeall@wiisglobal.org